Joy Bangla : A Collective History

Joy Bangla translates to ‘Victory for Bangla’ or ‘Hail Bangla’.

Originally published on 21st October 2023 from my website shumaiyakhan.com. Written during the early days of the Gaza Genocide when the piece ‘Daily Sugar’ was chosen as part of The Affordable Art Fair’s Abstract Spotlight wall - oct 2023 london edition. Largely inspired by my grandmothers, death and grieving a few personal moments in my life which I have only shared in private recently.

I’ve thought about republishing this for a while as Bangladesh is going through it’s current revolution (still) even after Sheikh Hasina’s departure. My current next issue of Substack is still being written as I review a painting and taking some time out of Instagram/platforms I’m better known on. I’ve refrained republishing this body of writing, as this was also the last normal conversation I had with my dad before the entirety of my family structure shifted. I understand only so much of what my Nanu (maternal grandma), aunts and uncles and my father who was about 4 years old experienced during the Bangladesh Genocide and Liberation War of 1971, and how these affects still live on. জয় বাংলা Joy Bangla.

I HEARD THE NEWS

There are too many prayers to count

My grandmothers are perishing

My father is moving frail

In my mind, I’m still 25

It rains everyday

Forests burn everyday

Women are missing in every way

There’s trouble written on paper

Old men are corrupting the youth

Old men are corrupting women

Old men are corrupting children

And young boys to become bitter

Older men, all before their time

My grandmas are perishing

All within their time

Taking away what time

They endured, they made happen

Leaving us with old men

In old politics and they say old ways

Old conventional, correct ways

My father is growing frail

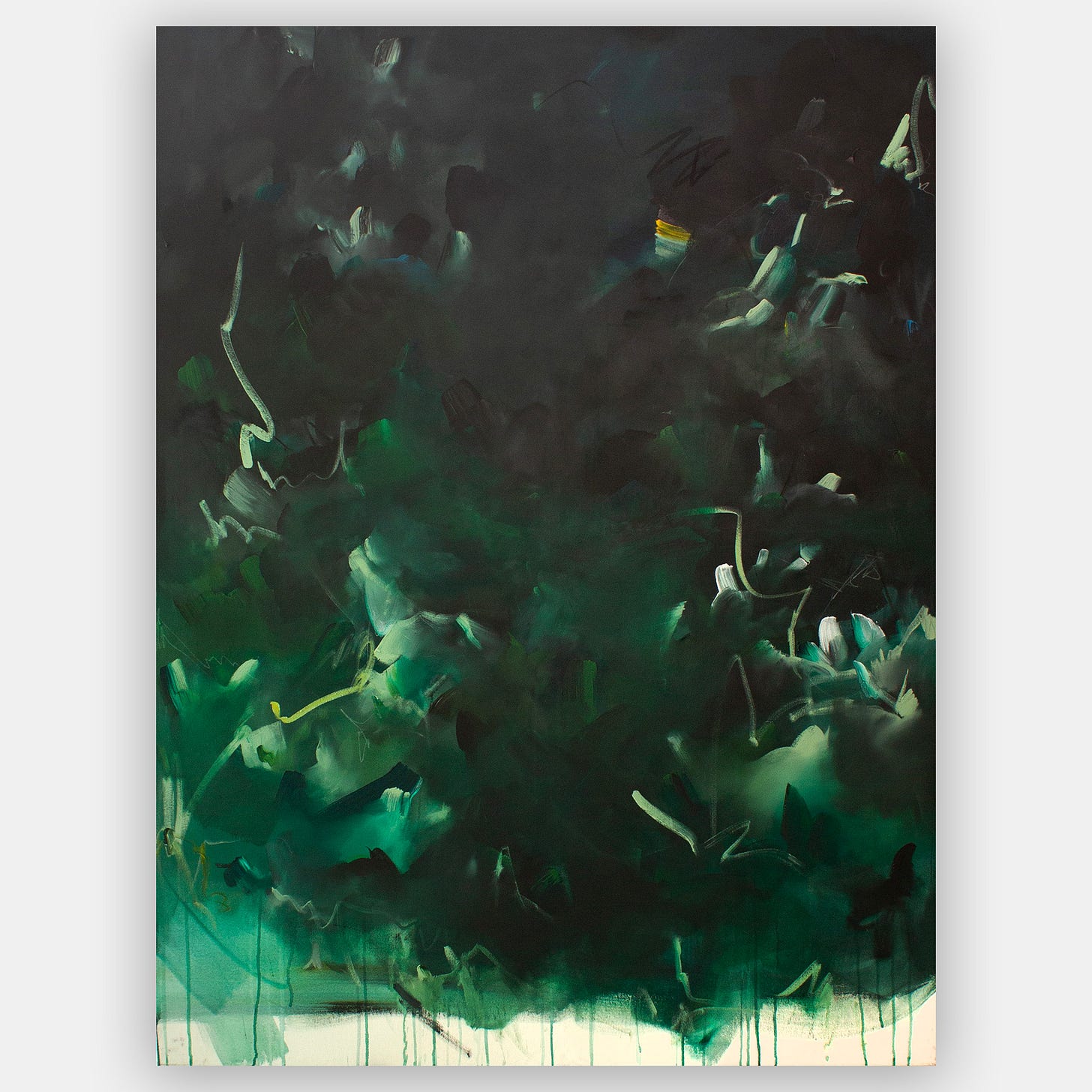

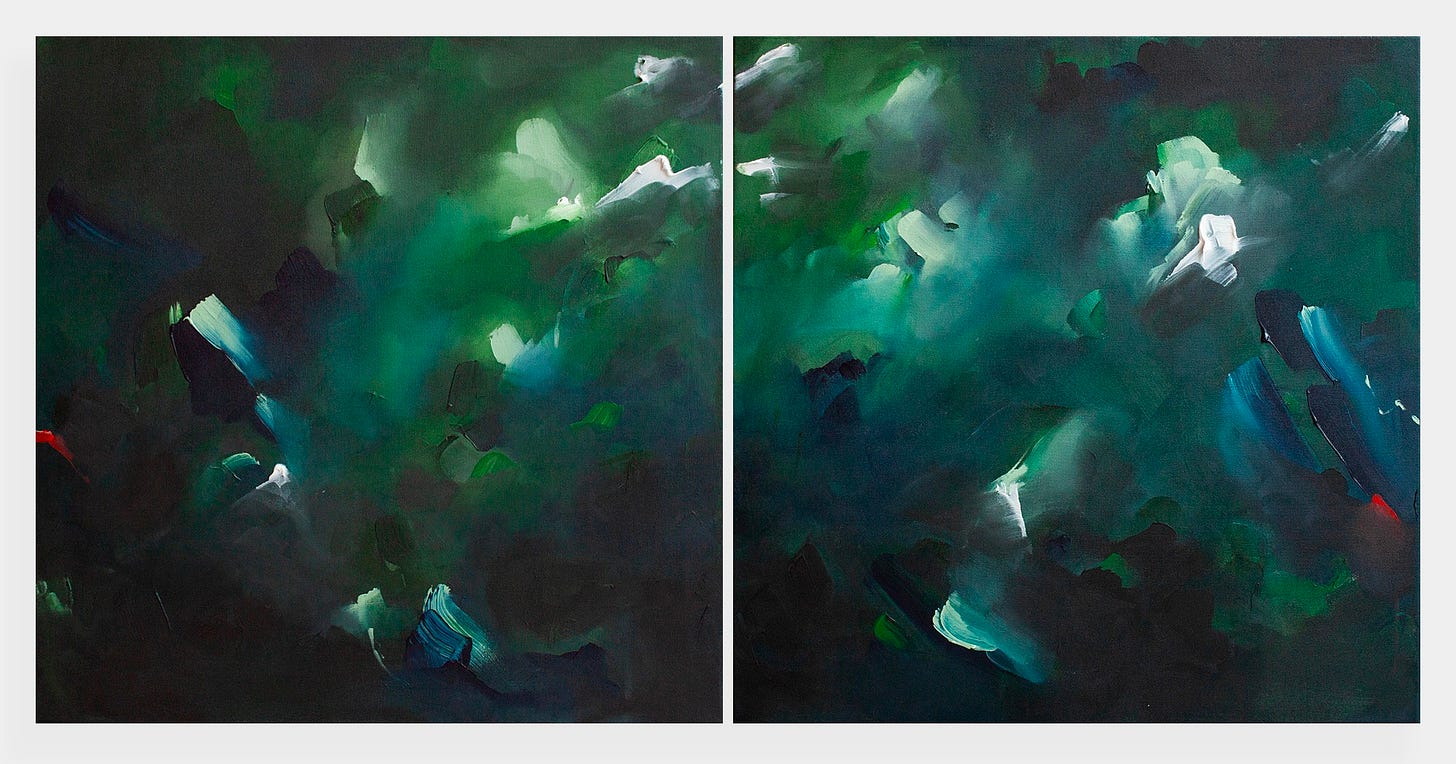

Daily Sugar, 2023. Acrylic, charcoal and gesso on raw cotton muslin. 80 x 80cm. On display at Affordable Art Fair’s Abstract Spotlight, Battersea, London. Autumn 2023.

Joy Bangla translates to ‘Victory for Bangla’ or ‘Hail Bangla’. This is not the first time I’ve written about this painting. The first was sharing some poetry in this context between myself as a younger woman and my grandmothers. Recently, this painting ‘Daily Sugar’ has been curated for Affordable Art Fair’s Abstract Spotlight Wall along with 3 other artists for their London Autumn edition 2023.

This recent attention to the work made me question more about what I wanted to share about the woman/women who inspired this series of works on muslin. My Dadu’s (paternal grandmother) life was not one of ease. She and all my grandparents had endured wars - The Liberation War in 1971, The Bengal Famine of 1943 where an estimated 2.1-3 million were killed, Partition of India and Bengal in 1947 due to a third party (Britain). My Nana had also served in WWII for Britain. The escalated political climate with Israel and Palestine over the past 1.5 weeks (75+ years and if you include the Balfour declaration about 106 years) share many commonalities with the Bangladesh Liberation War, which caused the genocide of 3 million people, 10 million refugees and 30 million internally displaced in 8 and half months, all at the hands of Pakistan; a less than perfect creation by Imperial Britain and colonialism.

The painting was produced when I was told that my Dadu was terminally ill with a malignant tumour. While the “different young woman” in me grappled with the well known Islamic fact, that this life is temporary and one of a test, I couldn’t fathom how such a strong, stubborn, wickedly humoured matriarch could have had this bestowed on her. I do believe she suffered for longer than we knew, like so many other women of her generation. She had maybe a year at best. She departed a little less than 8 months later early September 2023. My last conversation with her, she had forgotten I was no longer 4yrs old and told my aunt I was very pretty - which if you knew our relationship, made me - and aunt - laugh. Nonetheless, I am thankful that was our last interaction.

My Amma (mum), aunts and I would often say how this generation of women were stubborn, and sharp-tongued. That’s all because they had to be. Many lost their husbands at a young age, many saw their children die due to lack of medical access and/or famine. The softness in them hidden as a means not to be vulnerable for hardship to fall again, but this softness still truly existed. Upon my Dadu’s death my mum shared with me memories she had of my Dadu before she got married. She was overly protective over her niece, kind and fierce. Dadu held no prisoners, she said what was on her mind unapologetically. I am a daughter of strong women. My Amma did not give birth to me, so she could watch her daughter be silent in any capacity.

When I make my paintings, drawing and poetry, I very rarely want there to be obvious links to my heritage. I don’t want my work to just be successful - or others to say it is successful because I’m a brown woman. Nor do I want the struggles faced by my community to be sensationalised for a western audience. As part of a Bengali diaspora, I aim to show other parts, normal, everyday human thought in my work. However, it is only natural that the history of my lineage, the way I’ve grown up, the women who’ve made me, hold some influence - good and bad - over me, in me. This isn’t unique to me; this happens through all cultures with every soul.

I think it’s important I speak about The Liberation War which occurred in 1971. When I decided I had to write about this painting, I contacted 3 key people. My Shaukat Mama (uncle) who’s an activist through and through and ex-Labour Councillor, my Nanu (maternal grandmother) who was alive during this time and my dear Baba. My uncle had always educated us on the logistics of the Liberation War. My Nanu could provide a clearer timeline from a first hand experience and Baba could tell me of my Dadu whom I know well but not her experience of the war(s) and my Dada, who passed away before I was born.

Bangladesh (Bengal), was also known as ‘Greater Bangladesh’ / ‘Brihottor Bangladesh’ was much larger 130 years ago, including West Bengal, Assam, Tripura and Manipuri to name a few. However, the British had split the state into 2, first in 1905, and then once again in 1947 only 2 days after partition on 17th August by Cyril Radcliffe, drawing a line between West Bengal which would remain a part of India for the Hindu majority, and east Bengal to be known as East Pakistan. It would be wise to mention, that Bangladesh is a secular country.

My Dadu would wear white starched cotton muslin saris ever since my Dada passed away. Today Bangladesh still produces Jamdani saris made from fine cotton and silk, laced with flat embroidery. Muslin, once a prized fine cotton fabric produced in Dhaka was globally shipped and purchased by the Egyptians and European aristocrats this industry saw Imperial rulers ban its production, break looms and subsequently the fingers and limbs of anyone who dared to produce the fabric. This very fabric is what this painting is made with.

The entire body of work is about the spiritual finding of oneself within the culture you have been gifted. The charcoal and colour green are evident throughout my works, when talking about my matriarchal lineage, spiritual connection, circles of life, death and, home in the physical and in the heart.

“British colonial masters divided our country in two parts. One part went to India and the other to Pakistan. A partition imposed on millions of Bengalis from the top. It is like Balfour declaration on Palestine.

Then in 1971, the Pakistani regime’s policy on East Pakistan was “we want the land but not the people living on it”. This is what occupying Israelis are saying. They want Gaza and West Bank but not the people (Palestinians) living on it.” There is so much similarity…..”

- Shaukat Ahmed, MBE.

A large number of Bengali intellectuals and academics were killed for demanding the right to have their native language Bangla as the state language - see Dhaka University Massacre of February 1952. Pakistan stated Urdu would be the language of the Islamic nation. This mandate was problematic not only for Bengalis, but for neighbouring majority Punjabi speakers. Therefore, we now have ‘International Mother Language Day’ on 21st February to safeguard all native languages and commemorate those who fought for their rights. Both my parents understand and can speak Urdu almost fluently. This is no accident. To further the cause of Urdu and eliminate Bengali as a language, systemic rape was put in play and entire villages were burnt to the ground as a means to ethnically cleanse the Bengalis and make them Pakistanis.

When asking my Baba of what he remembered as a child who’d lived through this time, he said my Dadu and her sisters would prepare food while my Dada would cook daily for the 100+ family members as well as the freedom fighters known as the Mukti Bahini, consisting of Bengali military and paramilitary personnel. Many women also joined the force. He said he remembers his uncle - my Nana’s brother and my Dada’s cousin, evacuating him, his siblings, cousins, and his father’s family to my Nana’s Bari (village) in Mohammedpur situated in the countryside, which still stands today. He recalls bomb shelters that were made to hide in. My Baba was 4.

When I spoke to my Nanu with Amma for aid, she gave me further details of how Amma was a new born when war broke out. She mentioned how extended members of our family had absconded from the Pakistani military to avoid worse fates. My Nana prior to March 1970 had been working night shifts in Bradford’s mills. He had growing concerns for his wife and his children’s safety as Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the elected President of the East Pakistan state, a known revolutionary and activist was imprisoned. Nana would send money to Nanu not knowing if any had been received. Slowly, he and his friends emptied their bank accounts as to stop Pakistani officials from ceasing assets and he returned to Bangladesh. While in Mohammedpur, vegetables were plenty in the village, however rice, meat and spices were scarce. There were whispers of Pakistani sympathisers and the village being infiltrated, to which my Nana ordered a boat for his wife, children, my Baba and his family to escape to Jamapur temporarily. My family was one of the luckier ones.

When asking my Baba and his sisters - they just happened to be on the call in the background - if their parents ever shared anything about partition, they said no.

Every year when Pohela Boishakh (Bengali New Year) comes around, my family celebrates with traditional food, poetry, arts, music and the wearing of red and white clothing. This is why I will never stop wearing cotton sarees or using muslin in my art.

So you see, the world has seen this happen many times after the Holocaust, including but not limited to Algeria, South Africa, Vietnam, Iraq and Bosnia, and more recently Xinjiang in China and currently Sudan, which we swore we would never allow to happen again.

These generations have seen more than I, my brother, cousins and friends ever will. We are here, alive and speaking Bangla because my forefathers resisted. Every time I look at this painting I’m reminded of the sacrifices my Dadu, Dada, Nanu and Nana made for us. I can’t help but shed a tear for them. It is my duty as their granddaughter to tell future generations what happened and to stand up for those who face similar oppression.

‘Daily Sugar’ is still available for purchase. 50% of proceeds will go towards Palestine Children’s Relief Fund. Contact for purchase.

Joy Bangla and Viva La Palestine.

-

I would like to thank Shaukat Ahmed for proof reading and teaching my generation about our heritage. My Baba Shuhan Khan, my Fufus Shumi (my name sake) & Ruhi Khan (paternal aunts), Shanaz Ahmed (Khala, maternal aunt), Syeda Lipu Ahmed (Amma) and Syeda Nessa Ahmed (Nanu) for their contributions and encouragement, always.